Journal of the Open Therapy Institute

Issue 2 | September 2025

Editorial Board

Andrew Hartz, PhD (Co-Editor in Chief) — Open Therapy Institute

Val Thomas, DPsych (Co-Editor in Chief) — Critical Therapy Antidote

Nafees Alam, PhD — University of Nebraska

Lawrence Amsel, MD, MPH — Columbia University

Joshua Aronson, PhD — New York University

Omar Sultan Haque, MD, PhD — Harvard University

Neil J. Kressel, PhD — William Paterson University

Dean McKay, PhD — Fordham University

Richard J. McNally, PhD — Harvard University

Pamela Paresky, PhD — Harvard University

Richard Redding, JD, PhD — Chapman University

Sally Satel, MD — Yale University

Michael Strambler, PhD — Yale University

Table of Contents

Introduction: The Emerging Movement | Andrew Hartz, PhD & Val Thomas, DPsych, Co-Editors in Chief

New Clinical Challenges

Self-Censorship Is Becoming a Mental Health Crisis | Chloe Carmichael, PhD

How Intensive Parenting Damages Childhood Mental Health | Camilo Ortiz, PhD and Matthew Fastman, PsyD

New Anxieties: The Fear of Being Cancelled | Dean McKay, PhD

Recovery from Transition: Psychotherapy with Detransitioners | Stella O’Malley, MA

Navigating Political Polarization with Individuals, Couples and Families | Linda Chamberlain, PsyD and William McCown, PhD

Overlooked Populations

Biases Against Men in Couples Therapy | Nafees Alam, PhD

Improving Mental Health Care for Police Officers | Kristopher Kaliebe, MD

Treating Patients Impacted by Anti-White Racial Aggression | Jaco van Zyl, MA

How Therapists Often Fail Religious Clients | Neil J. Kressel, PhD

Black Sheep and Double Binds: Treating Minorities with Heterodox Viewpoints | Lawrence Ian Reed, PhD

Biases in the Field

Why Therapy with Men Must Recognize Biological Sex Differences | William C. Sanderson, PhD

How Socio-Political Values Shape the Therapeutic Alliance | Nina Silander, PsyD

Cultural Misunderstandings: On the Misuses of the Term “Culture” | Douglas Novotny, PhD

Codifying Bias: How Activist Politics Became Embedded in Social Work Standards and Practices | Nafees Alam, PhD

Introduction: The Emerging Movement

Over the past decade, we’ve seen politicized institutions profoundly impact people’s lives, such as with speech codes, hiring discrimination, and ideological training in schools and the workplace. Marriages have ended, friendships have been broken, and family members are estranged. It’s clear that people care deeply about political issues and are significantly impacted by them. It’s also clear that people have great difficulty talking about these issues productively. These topics can lead to emotion dysregulation, interpersonal conflict, cognitive distortions, defense mechanisms, and even symptoms of mental illness.

Sadly, at a time when psychotherapy professions could be helpful for people with these issues, the field has succumbed to the same politicized dynamics that have occurred elsewhere, including shutting down dialogue, promoting activism over patient-centered care, and even pathologizing patients for their views or immutable characteristics. As a result, profound damage has been done to the profession, mistrust is at a high, and millions of patients are struggling to find a therapist who respects their values and understands their concerns.

Now, there seems to be an opening for dialogue and reform. As more people become tired of conflict, they’re looking for ways to move forward. This is an opportunity we shouldn’t miss, but correcting the field is an enormous undertaking. This involves more than just telling therapists to refrain from attacking their patients over politics; it requires helping therapists understand and empathize with the myriad groups of people they often ignore or view negatively.

Fortunately, these biases are finally being confronted. A dynamic and enterprising new professional community is emerging: a robust network of academics and practitioners committed to reform. They aren’t just exposing specific biases; they’re creating the institutional structures necessary to sustain lasting change. Frontiers in Mental Health is providing a platform for their pioneering work.

The second issue of this journal contains 14 new articles, each on an issue that affects countless people but is neglected because of the social political biases in the profession. Chloe Carmichael highlights how self-censorship damages mental health. Jaco van Zyl explores the common but almost entirely avoided topic of anti-white racial aggression, and Dean McKay describes the increasing prominence of a new type of anxiety disorder that focuses on the fear of being canceled. Each article offers insights and evidence and highlights areas where more research and more clinical resources are needed.

Several articles deal with couples’ and family issues. Nafees Alam identifies biases against men in couples’ therapy. Camilo Ortiz and Mathew Fastman discuss the myriad costs associated with intensive parenting, while Linda Chamberlain and William McCrown consider how political conflicts impact families.

Other populations that often encounter bias include: police officers (Kristopher Kaliebe), religious patients (Neil Kressel), detransitioners (Stella O’Malley), and various minority group members who have heterodox beliefs (Lawrence Ian Reed). Finally, several articles discuss broader biases in the profession, such as the problem of ignoring biological sex differences (William Sanderson), the importance of socio-political values for the therapeutic alliance (Nina Silander), the misuse of the term “culture” inside and outside the mental health profession (Douglas Novotny), and biases that have become codified in the social work profession (Nafees Alam).

Each of these topics has the potential to grow into a substantial research program or clinical specialty in its own right. These articles are intended to start conversations, not end them. Further research, training, and service improvements are needed on each. Hopefully, these authors’ insights will serve as a catalyst to spark broader research, enhance training, and improve therapeutic services for millions of people.

— Andrew Hartz, PhD & Val Thomas, DPsych, Co-Editors in Chief

Self-Censorship Is Becoming a Mental Health Crisis

By Chloe Carmichael, PhD

More and more, therapy clients are arriving not with buried childhood traumas or abstract existential worries, but with a simple, gnawing problem: they’re afraid to speak their minds. It’s not stage fright or fear of public speaking. It’s the quiet, chronic fear of saying the wrong thing in a conversation with a friend, coworker, or family member and facing social or professional consequences. What we’re witnessing is more than a political or cultural shift—it’s a mental health trend.

As a clinical psychologist, I’ve seen how internal gag orders, whether imposed by political polarization, fear of mislabeling, or cultural confusion over what counts as “harmful speech,” can erode a person’s mental clarity, self-trust, and relationships. Free speech is not just a legal issue—it’s a psychological one, and the effects of suppressing it are showing up in therapy rooms across the country.

How Self-Censorship Shows Up in Mental Health Treatment

Fear of speaking up, rooted in social pressure, manifests in therapy in subtle but damaging ways. Clients describe withholding their opinions on sensitive topics, even from their therapists, for fear of judgment (Blanchard & Farber, 2015). Others share that they nod along in conversations where they feel uncomfortable, repressing discomfort to maintain social harmony. Over time, this pattern of self-silencing can erode self-efficacy and self-esteem (Tran, 2024).

Clinical research underscores the psychological toll of chronic self-silencing. For example, research on reflective verbalization suggests that articulating thoughts—even privately through journaling (Zheng, Lu, & Gan, 2019)—can significantly enhance insight and problem-solving (Wetzstein & Hacker, 2004). Conversely, habitual suppression of one’s views in social interactions can lead to emotional numbing and diminished self-efficacy. Research also shows that emotionally charged conversations, such as those involving politics, which are common sources of personal strain for many clients, can activate automatic emotional responses, making it harder to process information rationally (Morris et al., 2003). This helps explain why many clients fear such discussions or freeze in moments of disagreement. The longer clients suppress their true thoughts and emotions, the harder it becomes to locate and express them authentically.

An example taken from my new book (Carmichael, 2025) involves a client who discovered through frank therapeutic conversation and journaling that his years of “going along to get along” at work had numbed his ability to grapple directly with anger about being excluded for promotions due to diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. He eventually stymied himself so much that he became repressed, stuck in denial and the inability to connect with much drive around his professional goals. He was introduced to journaling as a way of articulating and questioning his thoughts, and this practice allowed him to gradually regain his voice and respond to the people and situations in his life more authentically and effectively. Another client felt fraudulent in her relationship with a beloved and strongly opinionated aunt. This client hid her political views to avoid being ostracized; her aunt had made it clear that anyone who voted like my client was “dead to her.” She benefited from using a suite of techniques, including the two listed below. Both clients found relief through open speech and the acknowledgment that their silence had come at an emotional and cognitive cost.

Helpful Therapeutic Solutions

Helping clients navigate the fear of speaking up requires more than telling them to speak up. Many already want to but feel paralyzed. Therapists need some strategies at their disposal—in particular, structured, step-by-step tools. Two effective techniques that can be used in clinical practice are the WAIT test and Say Your Line (Carmichael, 2025).

The WAIT Test

WAIT stands for Want, Appropriate, Inoculate, Trust. It helps clients think through whether, when, and how to speak up. The client is given the following directions:

W—Want: Ask yourself, “Do I really want to speak up?” Not every situation requires a response. For instance, if you’re tired and drained at the end of a long day, it might be okay to let a comment slide. But if you feel your silence is eating at you later, it’s a sign that your authentic self wants to be heard.

A—Appropriate: Is this the right time and place? If you’re about to bring up a politically charged topic with your new partner, it may be better to do it over a quiet dinner than at a noisy gathering. Choose a setting that allows space for a meaningful exchange.

I—Inoculate: Give the other person a small dose of what you want to say before you go all in. This might sound like, “Hey, I’d like to share something that may be a little different than what you’re used to hearing, but I’m hoping we can talk about it openly.” This primes them to receive your point without feeling blindsided and gives you a chance to see how they react to you sharing a little bit before you dive in deeper.

T—Trust: Ask yourself: “Do I trust this person or at least trust myself to handle the fallout if the conversation doesn’t go well?” You may not be able to control how others respond, but you can decide that even if it’s hard, you’ll have your own back.

Using the WAIT test before entering a difficult conversation helps reduce impulsive speech driven by frustration or anxiety. It also builds confidence by showing clients that they have a plan.

Say Your Line

Sometimes the most challenging part of speaking up is just getting started. The Say Your Line technique helps clients overcome that first hurdle by focusing only on the opening sentence or two of a difficult conversation. It draws on the cognitive-behavioral therapy tool of cognitive rehearsal, but zeroes in on the moment of initiation. The client is directed step-by-step using the following instructions:

Choose your line: Think about what you want to say, then craft one or two simple sentences that express it clearly and calmly. For example: “Actually, I see it differently—would you like to know why?” or “There’s something I’ve been meaning to say that’s a little sensitive but important to me.”

Imagine you’re an actor: Instead of emotionally gearing up for a high-stakes confrontation, shift your mindset. Pretend you’re an actor whose only job is to deliver a line. This can help remove the emotional weight and make it easier to simply speak.

Practice out loud: Say the line aloud a few times in a neutral tone, like you’re rehearsing a part. This builds familiarity and reduces pressure.

Deliver it: When the moment comes, don’t try to think through the entire conversation. Just take a breath and say your line. Once you’ve begun, you can move naturally into the rest of the dialogue.

Say Your Line is ideal for clients who already feel reasonably prepared, but who freeze up at the starting gate. It offers a quick on-ramp into dialogue without needing to map out every possible outcome. For clients who have done deeper work (e.g., using the WAIT test), this technique helps put their preparation into motion.

Conclusion: Reclaiming Speech as a Mental Health Imperative

Speech is more than communication; it’s a cognitive and emotional lifeline. When we silence ourselves, especially habitually and around deeply held values, we risk compromising our mental health. Therapists have a role to play in naming this issue and offering tools to help clients reclaim their voices. Encouraging open dialogue, practicing self-awareness, and equipping clients with simple and effective techniques can foster both personal growth and relational healing.

In a time when many feel they must choose between silence and exile, reclaiming our voice isn’t just a therapeutic task—it’s a cultural imperative. Whether you’re in the therapy room or across the dinner table, the ability to speak openly, without fear of exile, is essential for personal well-being and a resilient society. This cultural silencing (Rudert et al., 2017) may also be one hidden contributor to the loneliness epidemic that public health leaders, including the U.S. Surgeon General, are urgently working to address.

References

Blanchard, M., & Farber, B. A. (2015). Lying in psychotherapy: Why and what clients don’t tell their therapist about therapy and their relationship. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 29(1), 90–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2015.1085365

Carmichael, C. (2025). Can I say that? Why free speech matters and how to use it fearlessly. Skyhorse Publishing.

Morris, J. P., Squires, N. K., Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2003). Activation of political attitudes: A psychophysiological examination of the hot cognition hypothesis. Political Psychology, 24(4), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9221.2003.00349.x

Rudert, S. C., Hales, A. H., Greifeneder, R., & Williams, K. D. (2017). When silence is not golden: Why acknowledgment matters even when being excluded. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217695554

Tran, C. (2024). Self-efficacy’s mediating role on the relationship between personality and depression in the unemployed [Master’s thesis, San José State University]. https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.gmg9-ykt5

Wetzstein, A. & Hacker, W. (2004). Reflective verbalization improves solutions—The effects of question‐based reflection in design problem solving. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18(2): 145–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.949

Zheng, L., Lu, Q., & Gan, Y. (2019). Effects of expressive writing and use of cognitive words on meaning making and post-traumatic growth. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 13, e5. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2018.31

How Intensive Parenting Damages Childhood Mental Health

By Camilo Ortiz, PhD and Matthew Fastman, PsyD

Parenting styles have shifted radically over the past few decades. But as parents spend more time with their children and pay more attention to their mental health, rates of childhood mental illness appear to be skyrocketing. How could this be? One possibility is that over-intensive parenting deprives children of opportunities to explore and build competence. While this approach to parenting is well-intentioned, it typically leaves parents exhausted and kids fragile and immature. This paper will outline this problem and propose solutions for both parents and therapists.

Background

Research indicates that parents have spent significantly more time with their children since the 1990s. For example, today’s working mothers spend as much time with children as stay-at-home mothers did in 1975. Such quantitative investigations align with qualitative reports of parents adopting more controlling behaviors, particularly among middle- and upper-class families.

This shift in child rearing, commonly referred to as helicopter parenting or parental overinvolvement, can be defined as a parenting style characterized by excessive participation in most of a child’s decisions, including those where parental action is inappropriate given the child’s level of development. Research suggests that overinvolved parenting is associated with poorer autonomy development, self-efficacy, and emotional regulation in children (Segrin et al., 2013).

There are several subtypes of overinvolved parents, the most common being the anxious-overinvolved subtype. Anxious parents are prone to overparenting because they often have heightened perceptions of risk, which leads to restrictive parenting, including less willingness to allow their children to play alone (Aziz & Said, 2012). A high trait level of anxiety can cause greater relief for that parent when they intervene. In other words, it is more rewarding for anxious parents to intervene because of the outsized relief they feel.

Parental overinvolvement can affect children in several ways, such as by modeling avoidance for their children. These behaviors could include:

By avoiding anxiety-provoking situations, parents may teach their children to behave similarly through vicarious learning.

Anxious parents are also prone to accommodate children’s avoidance of difficult or anxiety-provoking tasks. Parental accommodation may facilitate children’s avoidance and safety behaviors by providing reassurance and validation and doing what children are afraid of for them.

Parental accommodation of child anxiety can include preemptive accommodations that are meant to help a child avoid anxiety-inducing situations (e.g., avoiding drop-off playdates for a child with separation anxiety), or they can include reactive accommodations that are intended to help a child escape an anxiety-inducing situation (e.g., ordering ice cream for a child who is afraid to walk up to the counter and order himself). While the relationship between parental accommodation and child anxiety appears to be bidirectional, it is also clear that these well-intentioned parental responses reinforce maladaptive coping mechanisms, impede corrective learning, and sustain elevated anxiety sensitivity (Lebowitz et al., 2015). The resulting short-term anxiety reduction of accommodation reinforces further dependence and avoidance in children, thus maintaining anxiety symptoms.

How Intrusive Parenting Shows Up in Psychological Clinics

The effects of overinvolved parenting on children can be widespread and profound. Parental overinvolvement is positively associated with anxiety severity in children (Rapee, 1997). Children of overinvolved parents are given fewer opportunities to handle challenging experiences independently, which in turn limits their ability to develop coping and problem-solving skills. This may increase their belief that they cannot tolerate stress and discomfort (Segrin et al., 2013). These skill deficits can turn normative childhood challenges into more serious mental health problems, as anxious avoidance can quickly feed on itself and rapidly increase in seriousness. For example, children who have normative and even healthy anxiety of speaking to strangers may begin to refuse all interactions with strangers, such as the parents of friends, extended family, and school personnel. These children may present for professional intervention when avoidance begins to interfere with functioning, such as in the case of school avoidance.

How Can Psychologists Provide Solutions?

Two psychological approaches for child anxiety have been demonstrated to be effective. The first, exposure therapy with blocked escape (Kendall et al., 2005), involves repeatedly facing feared stimuli and is meant to deliberately violate negative expectancies of harm, decontextualize inhibitory associations, and increase tolerance of distress (Craske et al., 2008). The second, parent accommodation-based approaches, such as Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (SPACE; Lebowitz et al., 2020), are meant to block parental involvement in reducing manageable child anxiety. Both approaches can be challenging for parents, particularly those who are concerned about seeing distress in their children. Children also commonly exhibit extinction bursts, which are behavioral and emotional escalations when parents set limits on accommodation. For example, children often throw tantrums if a parent attempts to prompt them to sleep in their own bed for the night, which can lead a parent to withdraw the directive. This can have the paradoxical effect of increasing parental accommodations to secure short-term relief from the child’s escalation.

A new treatment for child anxiety, Independence-Focused Therapy (IFT), targets overparenting by leveraging children’s universal desire to do things independently (Ortiz & Fastman, 2024). In this treatment, children indicate which independence activities (IAs), such as riding a bike to the park alone, shopping for food alone, and taking a train alone, they would like to do. Parents are not present during IAs and, therefore, cannot intrusively intervene. Recent compelling evidence suggests that exposure therapy has beneficial effects on stimuli that are not even in the same fear category as the fears being targeted. For example, exposure to spiders improved anxiety of heights in participants who had phobias of both (Kodzaga et al., 2023). It is precisely this dissimilarity that may make IAs more acceptable to children, their parents, and clinicians. For example, a child with a fear of the dark who is allowed to ride his bike to the park alone may experience a reduction in his fear without ever directly exposing him to the dark. This is due to the shared underlying mechanisms operating in both cases. Preliminary data suggest that daily IAs lead to less anxiety in children and greater confidence by their parents that they are capable. Recent data (Inserra & Ortiz, 2025) found that parents reported IFT to be equally acceptable as a treatment to traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy. Further research is needed to examine the long-term effects of IFT and moderators on treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

The rise of intensive or overinvolved parenting appears to be an important cause of rapidly increasing rates of child anxiety. Evidence-based approaches, such as exposure therapy and reducing parental accommodations, are insufficient to reverse this troubling increase. Novel approaches, such as IFT, that are rapidly scalable and have lower training requirements, are a promising approach to help these children and their parents.

References

Aziz, S., & Said, A. (2012). Parental anxiety and risk perception: Implications for restrictive parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(6), 950–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9567-3

Craske, M. G., Kircanski, K., Zelikowsky, M., Mystkowski, J., Chowdhury, N., & Baker, A. (2008). Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003

Inserra, A., & Ortiz, C. (2025). Treatment acceptability of independence-focused therapy and exposure therapy [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Long Island University-Post.

Kendall, P. C., Hudson, J. L., Gosch, E., Flannery-Schroeder, E., & Suveg, C. (2005). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety-disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(1), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.135

Kodzaga, I., Dere, E., & Zlomuzica, A. (2023). Generalization of beneficial exposure effects to untreated stimuli from another fear category. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), 401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02698-7

Lebowitz, E. R., Marin, C., Martino, A., Shimshoni, Y., & Silverman, W. K. (2020). Parent-based treatment as efficacious as cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety: A randomized noninferiority study of supportive parenting for anxious childhood emotions. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(3), 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.02.014

Lebowitz, E. R., Scharfstein, L. A., & Jones, J. (2015). Comparing family accommodation in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and non-anxious children. Depression and Anxiety, 32(12), 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22451

Ortiz, C., & Fastman, M. (2024). A novel independence intervention to treat child anxiety: A nonconcurrent multiple baseline evaluation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 105, Article 102893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2024.102893

Rapee, R. M. (1997). Potential role of childrearing practices in the development of anxiety and depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 17(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00040-2

Segrin, C., Woszidlo, A., Givertz, M., & Montgomery, N. (2013). Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(6), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2013.32.6.569

New Anxieties: The Fear of Being Cancelled

By Dean McKay, PhD

Akyrono (ακυρώνω )—from Greek, meaning “to nullify”

As society becomes increasingly polarized, people are being pressured to align themselves publicly with the currently accepted political narrative. It is not surprising that self-reported anxiety states are rising. In this essay, I will be arguing that these punishing social conditions are now in danger of generating new mental health disorders. In this essay, I argue that one particular anxiety disorder variant is becoming apparent, characterized by an irrational fear of being canceled. I am therefore naming this “akyró̱no̱phobia,” derived from the Greek meaning “to nullify.”

Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in the general public, with estimates suggesting that close to 20% of the public will have had serious anxiety within the past year and that just over 34% will experience it during their lifetimes (Szuhany & Simon, 2022). Although the current diagnostic manual lists obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in a separate category, that condition is also marked by significant anxiety and afflicts around 2% of the population (Pampaloni et al., 2022). Collectively, this means that approximately 66 million Americans will suffer from an anxiety disorder or OCD in the next year.

Experts in anxiety disorders and OCD have begun to recognize a specific manifestation, marked by intense and exaggerated fears of being canceled. I recently engaged colleagues on an expert network regarding how frequently they have treated individuals with fears of being canceled. This informal polling showed that of 187 colleagues, 147 reported anywhere from two cases to dozens who report this specific fear. The symptoms associated with this fear have included such diverse behaviors as avoiding social interactions and online conversations, destroying emails received from others if the individual remotely suspects it has upsetting content, and seeking reassurance from past consensual sexual partners that their intimacy was, in fact, appropriate. This is not an exhaustive list, but one common thread is that the sufferers generally possess personal qualities that make them particularly low risk for committing any act that might be deemed suitable for cancelation in the online social ecosystem. Specifically, most people with OCD typically have higher levels of neuroticism, a personality trait that makes people risk-averse (Barlow et al., 2014).

The Nature of Akyró̱no̱phobia

In proposing this phobia, it is reasonable to suggest it is characterized by two different patterns of psychopathology. One pattern may be obsessive-compulsive thoughts about the risk of cancelation and compulsive behaviors to ward off these risks. The other may be generalized anxiety, with worries about actions that might result in cancelation, with a dominant anxious mood and associated physical consequences (i.e., muscle tension or gastrointestinal distress).

Considering the high-profile figures who have been canceled, it is little surprise that individuals prone to experiencing anxiety would suffer fears of it happening to them. To illustrate, if one were to simply Google the search term “people who were canceled,” it results in lists of public figures who were canceled stratified by year. It is such a pervasive social phenomenon that it is annually summarized. The manifestation of most anxiety conditions is embedded in the social context in which people live. The nature of akyró̱no̱phobia may be categorized into two different types.

Obsessive-Compulsive Type Akyró̱no̱phobia

Obsessions are characterized as intrusive and unwanted thoughts that the sufferer recognizes as irrational. These thoughts lead to considerable avoidance of situations that might provoke them and may or may not result in compulsive behaviors. Research has shown that OCD is highly heterogeneous, marked by subtypes (McKay et al., 2004; Wheaton et al., 2015). One facet of OCD that makes it a condition highly susceptible to akyró̱no̱phobia is that obsessions are typically a result of socially unacceptable ideas or situations that are widely held concerns by the public. To illustrate, whenever a serious illness gets media attention (such as COVID-19), individuals with OCD are more likely to express extreme concerns over contracting that condition (Sheu, McKay, & Storch, 2020).

This means that the social milieu is ripe terrain for obsessional content. When public figures face cancelation, experts in OCD can (and do) expect to see clients reporting intrusive thoughts that the same fate may await them. These individuals suffer greatly, as the offenses that drive their obsessions are very minor and would not be considered offenses for most. For example, in my anecdotal poll of colleagues, one commented that it was not uncommon for clients they had treated to scrub their computers of any emails they received that they thought might contain slightly offensive content. Some severe cases have even involved avoiding people out of concern that they might have an offensive thought in their presence. All of these obsessions are for thoughts, with no intent to commit any even remotely offensive actions or to utter any offensive remarks.

Generalized Anxiety Type Akyró̱no̱phobia

While obsessions over the risk of acting on offensive and unwanted thoughts is a well-known variant of OCD, akyró̱no̱phobia can also prompt serious worries that are associated with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Unlike OCD, the concerns associated with akyró̱no̱phobia are marked by reviewing past statements, emails, social media posts, and other public comments for the slightest potential for offending content. As with any worries, a prevailing challenge for sufferers is intolerance of uncertainty (Jacoby, 2020). The pain of this variation of akyró̱no̱phobia is that individuals can point to specific acts that they interpret as potentially offensive, connect these to acts of other public figures, and claim that their offenses are on par with the ones that resulted in others being canceled.

Treatment, Policy, and Politics

The above illustrations of how cancel culture can result in significant OCD or GAD manifestations that I have termed akyró̱no̱phobia should be viewed as cautionary tales of how public discourse and mob-inspired desires for retribution can inflict pain and suffering indirectly on innocent individuals. It also should be considered an area where redress is possible.

On a granular level, people with akyró̱no̱phobia can benefit from existing treatment approaches, so long as these are used with care. Exposure therapy is commonly prescribed for fears and OCD, and akyró̱no̱phobia would be no exception. It is essential that specific attention be given to social forces to ensure exposure is conducted not only ethically but also safely in the current social climate (as discussed in the context of COVID-19-related exposure in Sheu, McKay, & Storch, 2020).

On a policy level, mental health professional organizations would do well to consider the extent to which their policies genuinely embrace pluralism. In my anecdotal poll of colleagues, several also cited prevailing attitudes among colleagues as potentially making clients feel less comfortable expressing putative offensive thoughts to their clinicians. Reorienting the profession to accept clients for the full range of ordinary human emotional and cognitive experiences will go a long way toward addressing this issue.

As for politics, the mental health professions can do far better in embracing pluralism as well. This would mean endorsing a sense of fairness for all and setting aside some troubling movements that would allow clinicians to issue judgments about how clients may or may not receive care (McKay & White, in press; Strambler, in press). The mental health professions can and should do better to prevent unwanted and painful anxiety conditions. Addressing the illiberal excesses of cancel culture would be a significant public health benefit.

A Look Ahead

The public is generally unaware of this, but the mental health professions are collectively engaged in an internal struggle over how to address politics, both during within-session discussions with clients and concerning the policies they establish for professional conduct. The presence of akyró̱no̱phobia illustrates one of many places where clinicians lack clear guidance in how to best proceed, given the political focus within the profession. There is a growing recognition that political processes in the profession have been unrestrained and have lacked clear guidelines. For example, there have been increasing concerns that the politicization of the American Psychological Association has led professional members of the profession to hold anti-Semitic attitudes that emerge from anti-Zionist political viewpoints. There have been calls within some mental health professional communities to explicitly screen clients for political views and reject those who hold positions contrary to clinicians. These two examples only scratch the surface and represent ill-formed and heavy-handed attempts to integrate political processes into professional activities. This is hardly surprising since mental health professionals are not formally trained in political discourse. It is hoped that as the professions effectively address this challenge, there may correspondingly be attention paid to akyró̱no̱phobia in a non-judgmental manner, allowing clinicians to feel less constrained in addressing the individual needs of clients who report this problem.

References

Barlow, D.H., Sauer-Zavala, S., Carl, J.R., Bullis, J.R., & Ellard, K.K. (2014). The nature, diagnosis, and treatment of neuroticism: Back to the future. Clinical Psychological Science, 2, 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613505532

Jacoby, R.J. (2020). Intolerance of uncertainty. In J.S. Abramowitz & S.M. Blakey (Eds.), Clinical handbook of fear and anxiety: Maintenance processes and treatment mechanisms (pp. 45–63). American Psychological Association.

McKay, D., Abramowitz, J., Calamari, J., Kyrios, M., Radomsky, A., Sookman, D., Taylor, S., & Wilhelm, S. (2004). A critical evaluation of obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: Symptoms versus mechanisms. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 283–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.003

McKay, D., & White, E.K. (in press). Philosophical errors and unintended harms in recrafting the foundation of counseling and psychotherapy: Comment on Sue, Neville & Smith (2024). American Psychologist.

Pampaloni, I., Marriott, S., Pessina, E., Fisher, C., Govender, A., Mohamed, H., Chandler, A., Tyagi, H., Morris, L., & Pallanti, S. (2022). The global assessment of OCD. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2022.152342

Sheu, J.C., McKay, D., & Storch, E.A. (2020). COVID-19 and OCD: Potential impact of exposure and response prevention therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102314

Strambler, M.J. (in press). Universalism is not white: Commentary on Sue et al. (2024). American Psychologist.

Szuhany, K.L., & Simon, N.M. (2022). Anxiety disorders: A review. JAMA, 328, 2431–2445. https://doi.org/10.47191/ijcsrr/V7-i7-53

Wheaton, M.G., Schwartz, M.R., Pascucci, O., & Simpson, H.B. (2015). Cognitive-behavior therapy outcomes for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Exposure with response prevention. Psychiatric Annals, 45, 303–307. https://doi.org/10.3928/00485713-20150602-05

Recovery from Transition: Psychotherapy with Detransitioners

By Stella O’Malley, MA

Over the past decade, gender dysphoria has emerged as one of the most complex and sensitive issues facing young people, families, and clinicians. There has been a sharp rise in adolescents seeking support for gender-related distress (Cass, 2024; Chen et al., 2016; Olson-Kennedy et al., 2016). Related to this change, many therapists report an overwhelming demand for thoughtful, well-informed therapy in this area and a dearth of providers offering it.

Since 2017, I’ve worked as a therapist and support group facilitator for families, detransitioners, transgender individuals, and those experiencing distress following medical transition. I’ve regularly met with individuals who feel isolated, regretful, and let down by the very systems that were supposed to help them. Despite the growing need for services, though, many therapists avoid this work due to political pressure and concerns about professional risks. Therefore, access to psychological care remains limited.

There is currently a tremendous need for services that provide non-medicalized, evidence-based approaches to gender-related distress. Patients struggling with these concerns should always be met with curiosity, compassion, and clinical integrity (Clark et al., 2024). Of course, these same principles apply to treatment with detransitioners and others experiencing distress related to a medical gender transition.

Increasing Numbers of Detransitioners

The decision to detransition often comes after years of psychological struggle, with many facing heightened suicidality during this uncertain stage. Social rejection and isolation are common, compounding the emotional burden (Vandenbussche, 2022).

Detransition appears to be on the rise, possibly due to the increase in medical transitions or the influence of the gender-affirming model, which is patient-led and centers on self-identification, often resulting in medical intervention (WPATH, 2022). However, limited research makes it difficult to determine precise causes.

As one piece of evidence, the Reddit forum r/detrans (which features stories, questions, and resources about detransitioning) had fewer than 1,000 members in 2019; today, it has over 57,000. Media reports now frequently feature detransitioners whose stories often involve regret, isolation, and irreversible medical outcomes (see below). These experiences demand greater attention from clinicians, researchers, and policymakers alike.

Vandenbussche (2022) surveyed 237 detransitioners and desisters—92% female and 8% male—recruited from online communities. Desisters are those who no longer identify as transgender without undergoing medical transition, while detransitioners have medically transitioned and later reversed their course. The study found that 70% attributed their gender dysphoria to underlying issues such as mental health struggles, trauma, or internalized homophobia, and many felt that they had been inadequately informed about the treatments they received.

Stories of detransition and desisting are compelling. Psychoanalyst Lisa Marchiano (2021) documented the case of Maya, a distressed adolescent with an eating disorder who underwent medical transition and later detransitioned. In the same article, Marchiano referenced Livia, a woman who regretted transitioning after undergoing a mastectomy at 20 and a hysterectomy at 21.

Similarly, Reuters (Respaut et al., 2022) profiled Max Lazzara. At 14, Max began questioning her gender identity and found affirmation through online communities. By 16, she had started testosterone, and at 18, she underwent a mastectomy. Although she initially felt relief, her mental health deteriorated further, resulting in renewed suicide attempts, substance abuse, and disordered eating. In 2020, she came to identify as a lesbian, ceased testosterone, and now regrets that medicalization was offered as the answer to her distress.

Meanwhile, the New York Times (Paul, 2024) recounts the story of Grace Powell, who, as a teenager, believed transition would resolve her distress over puberty, bullying, and depression. She began cross-sex hormones at 17 and later had a double mastectomy. Yet, no one explored her underlying issues, including past trauma, before affirming her transition. She has since detransitioned and expresses regret.

Paul also profiles Kasey Emerick, who grew up in a conservative Christian community and transitioned to escape the stigma of being a lesbian. After five years living as a trans man, Emerick realized her mental health had worsened, detransitioned in 2022, and faced intense online backlash.

Littman (2021) found that 55% of 100 detransitioners reported inadequate evaluation before transitioning, 38% linked their dysphoria to trauma, abuse, or mental health issues, and 23% cited homophobia or difficulty accepting their sexual orientation as contributing factors in both transitioning and detransitioning. Similarly, Vandenbussche (2022) reported that 52% of detransitioners and desisters expressed a need to cope with internalized homophobia. These findings highlight the importance of addressing underlying psychological issues in therapy, rather than reinforcing the belief that medical transition is the only path forward. However, internalized homophobia is just one of many challenges detransitioners face. Unacknowledged comorbidities also pose significant barriers to recovery and wellbeing.

Challenges Facing Detransitioners

My work with detransitioners has been some of the most meaningful, and at times harrowing, of my career. The individuals I’ve worked with typically view their medical transition as a form of self-harm and deeply regret the hormonal and surgical interventions they underwent, highlighting the potential risks of medicalization.

I regularly hear from individuals who deeply regret undergoing hormonal treatments, mastectomies, vaginoplasties, hysterectomies, and other irreversible procedures. Detransitioners remain a minority within a minority, and yet their voices must be heard to fully understand the realities of gender dysphoria.

The consistent stories I encounter underscore the urgent need to approach gender dysphoria with caution, compassion, and a focus on long-term wellbeing (Littman et al., 2021, 2024; O’Malley & Bell, 2024). Internalized and externalized homophobia is a recurring theme in my clinical work. Many young people who later identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual describe struggling to accept their same-sex attraction and now regret pursuing medical transition as a way to “trans the gay away,” a phrase commonly used online to describe this phenomenon.

Physical complications from medical transition are a constant source of distress for group participants. Pain, incontinence, osteoporosis, and cardiac issues are frequently mentioned. Along with deep regret over harmful medical interventions and sadness over lost years, these challenges create an almost unbearable burden. The age range of participants is striking, spanning from 18 to 85 years old.

Conclusion

As awareness of detransition grows, so too must our willingness to listen without defensiveness or ideological bias. Those who regret their medical transition are not anomalies or statistics; they are people whose experiences expose critical gaps in our clinical practices, health care systems, and cultural assumptions.

We owe it to these individuals to take their experiences seriously. This means investing in robust psychological support, ensuring proper assessment and informed consent, and creating space for identity exploration without rushing to medicalization. Above all, this role requires compassion—not just for those who transition, but also for those who choose a different path.

References

Cass, H. (2024). Independent review of gender identity services for children and young people. The Cass Review. https://cass.independent-review.uk/home/publications/final-report/

Chen, M., Fuqua, J., & Eugster, E. A. (2016). Characteristics of referrals for gender dysphoria over a 13-year period. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 369–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.11.010

Clark, C., Pluckrose, H., O’Malley, S., & Miller, A. (2024, November 13). Our position FAQs. Genspect. https://genspect.org/our-position-faqs/

Littman, L. (2021). Individuals treated for gender dysphoria with medical and/or surgical transition who subsequently detransitioned: A survey of 100 detransitioners. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(8), 3353–3369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02163-w

Marchiano, L. (2021). Gender detransition: A case study. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 66(4), 813–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5922.12711

Olson-Kennedy, J., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Kreukels, B. P. C., Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L., Garofalo, R., Meyer, W., & Rosenthal, S. M. (2016). Research priorities for gender nonconforming/transgender youth: Gender identity development and biopsychosocial outcomes. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Obesity, 23, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1097/MED.0000000000000236

O’Malley, S. & Bell, K. (2024, March 12). We need to complexify our understanding of transition and detransition. Genspect. https://genspect.org/we-need-to-complexify-our-understanding-of-transition-and-detransition/

Paul, P. (2024, February 2). As kids, they thought they were trans. They no longer do. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/02/02/opinion/transgender-children-gender-dysphoria.html

Respaut, R., Terhune, C., & Conlin, M. (2022, December 22). Why detransitioners are crucial to the science of gender care. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-transyouth-outcomes/.

Vandenbussche, E. (2022). Detransition-related needs and support: A cross-sectional online survey. Journal of Homosexuality, 69(9), 1602–1620. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.1919479

World Professional Association for Transgender Health. (2022). Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people (Version 8). WPATH. https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc8/

Navigating Political Polarization with Individuals, Couples and Families

By Linda Chamberlain, PsyD and William McCown, PhD

Mental health professionals are increasingly confronted with the impact of political polarization on our clients’ most important relationships. Therapists are faced with how partisanship is straining family bonds: Clients cancel holiday gatherings, avoid dating people with opposing views, and endure long-term estrangements over ideological differences. As these issues surface in clinical settings, mental health professionals must be equipped to navigate the relational damage caused by political polarization. What can we do to help?

The Family System Under Stress

“My fiancé broke off our engagement. She knows I’m a conservative, but we got in a huge argument about deporting illegal immigrants, and she lost her mind. She called me a racist and colonizer, whatever that means. She’s been getting more radical about her liberal beliefs, and it’s finally wrecked our relationship. This feels so unfair.” (28-year-old male)

Finding a person to date has always been challenging, and the ideological divide between men and women adds to the complexity of this issue. We know that over the last few decades, men have tended to lean toward the Republican Party (52%), while women have leaned toward the Democratic Party (51%) (Pew Research Center, 2024). This small gap, however, is becoming a canyon. The gender divide is even more pronounced in Gen Z (born 1997–2012), with women becoming significantly more liberal and men becoming somewhat more conservative (Yale University, 2025).

Increasingly, couples who don’t share a political orientation are challenged to negotiate their differences or experience deep divides in their relationship, potentially resulting in separation.

“We finally stopped going out socially with our friends. Someone would always bring up something political, and we would get into an argument with each other. Now, we mostly sit in separate rooms at home watching different news stations or see our friends separately. I don’t want this.” (Wife married 24 years)

The impact of political discord extends beyond couples. Parent-child estrangements are increasingly common, with political disagreements sometimes acting as stand-ins for deeper emotional rifts.

“I just can’t believe that my mother voted for that man! It’s like she was blinded and couldn’t see who he is. I can’t be around her. That’s lasted for two years, and I can’t seem to forgive her.” (24-year-old female college student)

Sibling relationships are particularly vulnerable, with partisanship exacerbating long-standing rivalries and differences. Politics is second only to conflicts over aging parents and inheritances in destroying sibling bonds (Safer, 2019). Political conflict often masks unresolved issues such as parental favoritism or divergent values that require therapeutic investigation.

Extended families are also fracturing under political stress. Even minor conversations about current events can escalate into personal attacks and mutual recriminations. Clients report dread over holiday gatherings, with some choosing isolation over potential confrontation. During the 2024 holiday season, more than seven out of 10 adults surveyed said they hoped to avoid political discussions with family members (APA, 2024). In response, a plethora of advice has appeared very recently on internet platforms, usually taking the form of pragmatic tips to avoid potential conflict.

Effective Therapeutic Approaches

In this landscape of heightened division, it is crucial for psychotherapists to work skillfully with clients whose lives are impacted by political polarization. Navigating these tensions in the therapy room requires sensitivity, adaptability, and a nonjudgmental stance, as political differences often serve as proxies for deeper relational wounds or unmet needs. A fierce argument that flares up about the imposition of tariffs, for example, may have little to do with the matter itself, but instead operates as a channel for childhood grievances about perceived favoritism within the family.

By fostering an environment where clients feel safe to explore their values and emotional responses without fear of invalidation or escalation, therapists empower individuals and families to develop empathy, resilience, and authentic connection. This work not only eases relational distress but also equips clients to engage more thoughtfully in a polarized world, promoting psychological well-being alongside social harmony.

Insights from Family Therapy

Family therapy is a particularly suitable approach for working with the conflicts arising in a politically polarized group. The family therapist views the family as a system that is maintained and affected by each participating member. In politicized families, differentiation of self would be a core goal. The work would focus on allowing individuals to preserve their identity and beliefs while staying connected. No more “All liberals/conservatives are idiots” confrontations.

The primary goal of the therapist is to work collaboratively with family members to foster family unity despite political differences. Therapists can support clients in developing emotional resilience, asserting personal values, and engaging with family members from a stance of curiosity and respect rather than animosity.

In order to help family members improve their relationships, the therapist would focus on the following:

Reframing political arguments as representations of unmet emotional needs

Identifying and interrupting dysfunctional cycles of blame and moral condemnation

Exploring family of origin influences and intergenerational patterns

Setting boundaries around political discourse and promoting mutual respect

Practical Tools for Clinicians

The insights into working with polarized relationships gained from Family Therapy are generally useful for clinicians. In all family relationships, Safer (2019) emphasizes prioritizing love over politics and avoiding attempts to convert each other. People who believe that “I love my family member more than I love my politics” can more easily maintain a respectful relationship. The following are some basic guidelines and goals:

Couples: Encourage open and respectful conversations about political beliefs and teach skills such as reflective listening and emotional regulation.

Parents and Children: Help family members express appreciation for shared connections and respect each other’s unique perspectives regarding political dissimilarity.

Siblings: Help siblings reconnect with positive memories and enduring qualities of family identity beyond politics.

The Extended Family: Help politically divided family members abandon angry rhetoric or moral condemnation and reconnect to the shared history and importance of family relationships.

And finally, therapists should be prepared to teach and model skills that foster constructive dialogue and reduce defensiveness. These include:

reflective listening and emotionally focused communication;

boundary-setting strategies to limit exposure to partisan media or conversations; and

practicing dialectical thinking to better understand different world views.

Conclusion

Political polarization in families is on the rise. This increase is a relatively recent phenomenon, and therapists need to be equipped to help clients navigate this difficult terrain in a healthy way. A particularly helpful source of knowledge and strategies is Family Therapy, an approach that can help clients understand that the bonds they share are stronger and more enduring than any ideological divide. All clinicians, no matter what their modality, can adapt these tools for their own practices, helping to heal the broader social fabric, one family at a time.

Resources

An example of therapy with a politically divided couple is available on YouTube: “Helping Loved Ones Divided by Politics” with Dr. Bill Doherty

This article is adapted by the essay authors, L. Chamberlain & W. McCown from a chapter in their book, Psychotherapy in the Age of Political Polarization published in 2025 by Routledge. All quotes are from the authors’ or colleagues’ clinical experiences.

References

American Psychological Association (2024, December 10). After a divisive election, most U.S. adults ready to avoid politics this holiday. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2024/12/avoid-politics-holiday

McCown, W., & Chamberlain, L. (2025). Psychotherapy in the age of political polarization: A guide for mental health professionals. Routledge.

Pew Research Center (2024, April 9). Partisanship by gender, sexual orientation, marital and parental status. https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/04/09/partisanship-by-gender-sexual-orientation-marital-and-parental-status/

Safer, J. (2019). I love you, but I hate your politics: How to protect your intimate relationships in a poisonous partisan world. Biteback Publishing.

Yale University (Spring 2025). Yale youth poll. https://youthpoll.yale.edu/spring-2025-results

Biases Against Men in Couples Therapy

By Nafees Alam, PhD

When a couple begins therapy, both individuals should expect that their voices will be heard equally and their relationship dynamics examined with fairness and insight. However, for many men, the experience of couples therapy has become an unexpected tribunal where their masculinity itself stands accused. A negative view of men, which increasingly characterizes the broader culture (Alam, 2025a), is now evident in the clinical space (Alam, 2025b) threatening to undermine relationship healing processes.

This essay examines how biases against men manifest in couples therapy through stereotyping, blaming, ignoring, or misunderstanding male experiences. It explores the origins of these biases, their implications for men and society, and how therapists can work to correct these deeply unhelpful prejudices.

Background

Couples therapy emerged when gender roles were rigidly defined. Early models reinforced these structures, positioning women as emotional nurturers and men as rational providers. Feminist critiques in the 1970s and 1980s rightfully challenged these limiting paradigms, and therapeutic practice evolved to recognize the harmful effects of restrictive gender expectations.

However, this necessary correction has been overcorrected in some contexts. The term “toxic masculinity” exemplifies this problem, as the phrase inherently casts hostility toward the entire group it modifies. While women can engage in harmful stereotypically feminine behaviors, we don’t use “toxic femininity” because it’s obviously derogatory toward women as a whole. This linguistic double standard reveals a deeper bias where masculinity itself is increasingly treated as pathology rather than a complex gender expression containing both constructive and potentially destructive elements.

The American Psychological Association’s Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men (2018) acknowledge the need for gender-sensitive approaches, yet implementation often falls short. Research by Seager et al. (2014) found that therapists are more likely to pathologize identical behavior when exhibited by male clients than female clients, suggesting systematic interpretive bias rather than individualized assessment.

How These Issues Play Out in Mental Health Treatment

In the therapeutic setting, biases against men manifest in several key ways:

Pathologizing typical masculine traits while failing to validate positive ones (Englar-Carlson and Kiselica, 2013). When men express emotions through action rather than words, this may be labeled as “emotional avoidance” rather than recognized as a different but equally valid emotional style. Masculine tendencies toward problem-solving are often framed as “avoiding intimacy” rather than legitimate approaches to connection.

Employing double standards in intervention (Alam, 2025a). When a woman withdraws from conflict, it may be interpreted as self-protection; when a man does the same, it is often labeled stonewalling. When a woman raises her voice, it might be seen as an appropriate assertion; when a man does so, it is frequently pathologized as aggression or intimidation.

Unconsciously assigning men the role of perpetrator and women the role of victim before understanding unique relationship dynamics (Alam, 2025a). This prejudgment appears in subtle ways: directing more challenging questions to the male partner, offering more empathy and validation to the female partner, or interpreting ambiguous situations through a lens that assumes male misconduct.

Engaging in “medical gaslighting” (Sebring, 2021), where men’s lived experiences are systematically invalidated. The man who insists his silence stems from feeling overwhelmed rather than a desire to control may be told he is “not being honest about his intentions.” The man who points out double standards may be accused of defensiveness rather than legitimate advocacy for fair treatment.

Possible Solutions

Anti-male bias in couples therapy does not work for men or women. Some possible solutions to correcting this contemporary bias include:

Develop training that explicitly addresses potential anti-male biases alongside other forms of prejudice. Therapists must recognize that masculine emotional expression may look different than feminine expression without being inherently deficient. Training should include case studies demonstrating how identical behaviors can be interpreted differently based on gender.

Develop and utilize assessment tools that account for diverse communication styles. Rather than expecting men to conform to feminine-typical modes of emotional processing, create validated instruments that recognize multiple paths to connection and healing, including activity-based interventions and solution-focused approaches.

Establish clear protocols for balanced intervention that ensure equal therapeutic attention and challenge to both partners. This includes structured approaches to questioning, validation, and confrontation that prevent unconscious gender bias from directing therapeutic focus.

Create male-friendly therapeutic environments by incorporating elements that research shows improve male engagement: clear structure, goal-oriented frameworks, and recognition of strength-based masculine traits alongside areas for growth.

Integrate routine bias checks into supervision and peer consultation. Regular case reviews should specifically examine whether gender biases are influencing case conceptualization and intervention choices.

Conclusion

Creating truly gender-inclusive therapeutic spaces requires courage from clinicians to examine their own biases, creativity to develop more flexible therapeutic approaches, and commitment to seeing each couple as unique individuals rather than representatives of their gender. It requires moving beyond simplistic narratives to recognize the complex reality that both men and women bring strengths and challenges to relationships (Capozzi, 2022).

By openly discussing and addressing biases against men in therapeutic spaces—just as we discuss biases against women—we create the possibility for more truly equitable treatment. The future of effective couples therapy lies not in taking sides in gender wars but in transcending them—creating spaces where both men and women can be seen, heard, and understood in all their complexity. Only then can therapy fulfill its promise of healing relationships rather than unconsciously reinforcing the divisions it aims to bridge.

References

Alam, N. (2025a, March 3). Why do so many men avoid mental healthcare? The urgent need for male-focused mental health campaigns and therapeutic approaches. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/pop-culture-mental-health/202503/why-do-so-many-men-avoid-mental-healthcare

Alam, N. (2025b, February 14). Man versus bear: Who is the safer companion in the wild? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/pop-culture-mental-health/202502/man-v-bear-who-is-the-safer-companion-in-the-wild

Alam, N. (2025c, February 12). Treating men like women—why men struggle in a mental health system built for women. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/pop-culture-mental-health/202502/treating-men-like-women

American Psychological Association, Boys and Men Guidelines Group. (2018). APA guidelines for psychological practice with boys and men. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/boys-men-practice-guidelines.pdf

Capozzi, F. (2022). A multi-level guide to work with male clients in couple and family therapy from a gender-critical perspective. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 34(1–2), 178–195. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/08952833.2022.2065766

Englar‐Carlson, M., & Kiselica, M. S. (2013). Affirming the strengths in men: A positive masculinity approach to assisting male clients. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(4), 399–409. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00111.x

Seager, M., Sullivan, L., & Barry, J. (2014). Gender-related schemas and suicidality: Validation of the male and female traditional gender scripts questionnaires. New Male Studies, 3(3), 34–54. https://newmalestudies.com/OJS/index.php/nms/article/view/151/154

Sebring, J. C. (2021). Towards a sociological understanding of medical gaslighting in western health care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 43(9), 1951–1964. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13367

Improving Mental Health Care for Police Officers

By Kristopher Kaliebe, MD

“Therapists are not your friend and really could care less about you as a person. Never ever talk to them. They are liberal scumbags, or they wouldn’t be in that career.”

This police officer’s overgeneralization recognizes that many therapists’ viewpoints are incompatible with a sympathetic and supportive view of the police. Recognizing this bias, this essay argues for the critical need to develop and implement effective strategies to remediate these negative views and promote effective mental health treatments for law enforcement officers.

Bias in the Mental Health Field Against Law Enforcement Officers

There appears to be widespread anti-police bias across the different professions involved in the mental health field, as the following examples would attest:

In 2022, the American Psychological Association formed a resolution on psychology’s role in “dismantling” racist policing (p. 1).

The Journal for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has declared itself to be an “anti-racist journal,” asserting that “We could fill these pages with the names of the Black people murdered by police officers, a devastating toll of racism in the United States.”

Social work is being shaped by social policy academics who support defunding the police. They argue that the police are tools of “social control and White supremacy” and that social workers should cease to collaborate with these agents enforcing racial dominance.

It is important to note that police officers’ overly negative portrayal is also influenced by a larger societal context that has adopted a social justice narrative. Three simplistic ideas are popular in mental health organizations and academia:

Traditional power structures are mostly harmful to society.

Discrimination is the fundamental cause of all unequal outcomes.

Problems should be seen primarily through the lens of race or gender or other markers of identity.

Such anti-police rhetoric, which is now well established in mental health institutions, professional bodies, and therapy services, is likely to influence therapists to:

view police as agents of oppression rather than unique individuals;

conceive of law enforcement officers with simplistic, false narratives; and

have reduced empathy toward officers.

What does this mean for police officers themselves? It is likely that this entrenched hostile rhetoric could undermine police officers’ trust in mental health professionals and discourage the use of employee assistance programs.

Mental Health Needs of Law Enforcement Officers

The mental health community should have the perspective that every law enforcement officer is an individual, requiring a personalized approach reflecting their needs, stressors, and treatment goals.

Therapists working with officers should consider the stresses of police work: trauma exposures, shift work, organizational stress, and disturbed sleep cycles. Law enforcement officers often interact with people at their worst. Police are scrutinized by the media and public and are easily criticized on social media. There is a reputational asymmetry; citizens and journalists can (and do) attack the reputations of officers by portraying their actions as misconduct (see here and here).

Yet, officers have few opportunities to explain their perspectives, and exoneration often takes years and does not make headlines. Police may have good benefits and adequate salaries, but they are certainly not rich. Judging by the mass exodus and lack of new recruits, the job of a police officer has become less appealing than ever.

Police may witness terrible traumas, and their work leads to increased rates of emotional distress when compared to the public at large. Officers often suffer from compassion fatigue, emotional numbing, and cynicism (Jetelina et al., 2020).

Most officers handle traumatic events well, but some develop severe trauma reactions, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (Corthésy-Blondin et al., 2022) along with work stress-related mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety. Shift work is also hard on families, and the public needs police around the clock, including holidays, meaning officers’ schedules often conflict with family routines and special gatherings.

Police officers require determination and toughness, values that are sometimes at odds with asking for help. Officers must determine if their symptoms will decline over time or if they would benefit from professional mental health care. Fortunately, the law enforcement community has made a laudable effort over time to erode the stigma that portrays those seeking mental health care as lazy or weak. Yet, due to the critical nature of law enforcement, police administrators have procedures to remove officers that may be a risk to themselves or the public. As such, officers may worry that seeking help may signal an inability to handle their job and thus risk their removal from active duty.

Promising Interventions to Improve Mental Health Care for Law Enforcement Officers

Given the particular needs of police officers seeking help, we can identify some potential helpful interventions. To start, innovative programs can combine technology with anonymous surveys to help find officers who are most likely to benefit and help them access services (Deng et al., 2024). Then, in the clinical setting, the following approaches could be helpful:

Motivational approaches should prioritize goal setting and barriers to change (Steinkopf et al., 2015).

Mentalization (the ability to notice, access, and reflect on mental states in oneself and others) is an important skill for police and may be both an important focus of training for interfacing with the public and an important focus in individual therapy (Drozek et al., 2021).

Group therapies, whether online or in person, show potential for destigmatizing mental health treatment, efficiently spreading treatment, and utilizing the benefits of the group process.

Cognitive behavior therapy approaches have been applied to police (Lees et al., 2019), as have solution-focused therapies (Pooley et al., 2021).

Police officers’ mix of physical and emotional stressors (Mumford et al., 2014) suggests that physical wellness programs are desirable to encourage healthy lifestyles and robust physical conditioning and reduce substance abuse.

Family and marriage counseling may be especially beneficial for those in law enforcement (Sharp et al., 2022).

Finally, none of the above approaches are likely to work if police officers do not trust their therapists. Police counseling referral networks need to create a supportive, collaborative, and confidential environment. It is important to ensure therapists are equipped to effectively collaborate with police officers. Therefore, specialized training programs and workshops should be developed to address the unique challenges and stressors faced by law enforcement personnel. This training should include:

a comprehensive understanding of police culture and experiences;

building skills in trauma-informed care, resilience-building techniques, and evidence-based approaches tailored for the police community;

contributions from approaches across a range of psychotherapy modalities;

incorporation of peer consultations or ride-alongs with current officers or training from former officers to provide therapists with practical insights into the experience of law enforcement; and

technological innovations to enhance engagement with programs to increase fitness and overall health.

Conclusions

Some mental health professionals promote negative views of police officers and morally elevate, promote, and apply police-hostile theories through aforementioned policy statements, training programs, and scholarly journals. Mental health professional organizations must condemn any anti-police rhetoric that is arising from within their own ranks. Therapists must exchange anti-therapeutic ideologies for intellectual humility, the open exchange of ideas, and a focus on helping individuals.

It’s tragic that, under the banner of mental health, ideology has been weaponized against the law enforcement community. To address this problem, mental health professionals and the organizations that represent them should espouse balanced, fact-based views toward law enforcement, including noting research that questions narratives about pervasive racism and acknowledging positive trends in policing and the criminal justice system (Fryer Jr., 2019; Lattimore, 2022; Mangual, 2022).

References

Corthésy-Blondin, L., Genest, C., Dargis, L., Bardon, C., & Mishara, B. L. (2022). Reducing the impacts of exposure to potentially traumatic events on the mental health of public safety personnel: A rapid systematic scoping review. Psychological Services, 19(S2), 80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ser0000572

Deng, Y., Frey, J. J., Osteen, P. J., Mosby, A., Imboden, R., Ware, O. D., & Bazell, A. (2024). Engaging law enforcement employees in mental health help-seeking: Examining the utilization of interactive screening program and motivational interviewing techniques. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–15. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/s10488-024-01384-0

Drozek, R. P., Bateman, A. W., Henry, J. T., Connery, H. S., Smith, G. W., & Tester, R. D. (2021). Single-session mentalization-based treatment group for law enforcement officers. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 71(3), 441–470. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.2021.1922083

Fryer Jr, R. G. (2019). An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. Journal of Political Economy, 127(3), 1210–1261. https://doi.org/10.1086/701423

Jetelina, K. K., Molsberry, R. J., Gonzalez, J. R., Beauchamp, A. M., & Hall, T. (2020). Prevalence of mental illness and mental health care use among police officers. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2019658. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19658

Lattimore, P. K. (2022). Reflections on criminal justice reform: challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 47(6), 1071–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-022-09713-5

Lees, T., Elliott, J. L., Gunning, S., Newton, P. J., Rai, T., & Lal, S. (2019). A systematic review of the current evidence regarding interventions for anxiety, PTSD, sleepiness and fatigue in the law enforcement workplace. Industrial Health, 57(6), 655–667. http://dx.doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2018-0088

Mangual, R. A. (2022). Criminal (in) justice: What the push for decarceration and depolicing gets wrong and who it hurts most. Center Street.

Mumford, E. A., Taylor, B. G., & Kubu, B. (2014). Law enforcement officer safety and wellness. Police Quarterly, 18(2), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611114559037

Pooley, G., & Turns, B. (2021). Supporting those holding the thin blue line: Using solution-focused brief therapy for law enforcement families. Contemporary Family Therapy, 1–9. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10591-021-09575-9

Sharp, M. L., Solomon, N., Harrison, V., Gribble, R., Cramm, H., Pike, G., & Fear, N. T. (2022). The mental health and wellbeing of spouses, partners and children of emergency responders: A systematic review. PLOS ONE, Jun 15;17(6):e0269659. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269659

Steinkopf, B. L., Hakala, K. A., & Van Hasselt, V. B. (2015). Motivational interviewing: Improving the delivery of psychological services to law enforcement. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(5), 348. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pro0000042

Treating Patients Impacted by Anti-White Racial Aggression

By Jaco van Zyl, MA

Racial discrimination, bias, or aggression toward people of any race is unethical. These experiences can impact people’s lives, leave lasting wounds, and negatively impact mental health. However, one form of racial aggression is often overlooked: aggression directed against people for being white. Although many clinicians have reported observing this phenomenon in their patients, training and clinical services on this issue are almost entirely nonexistent.

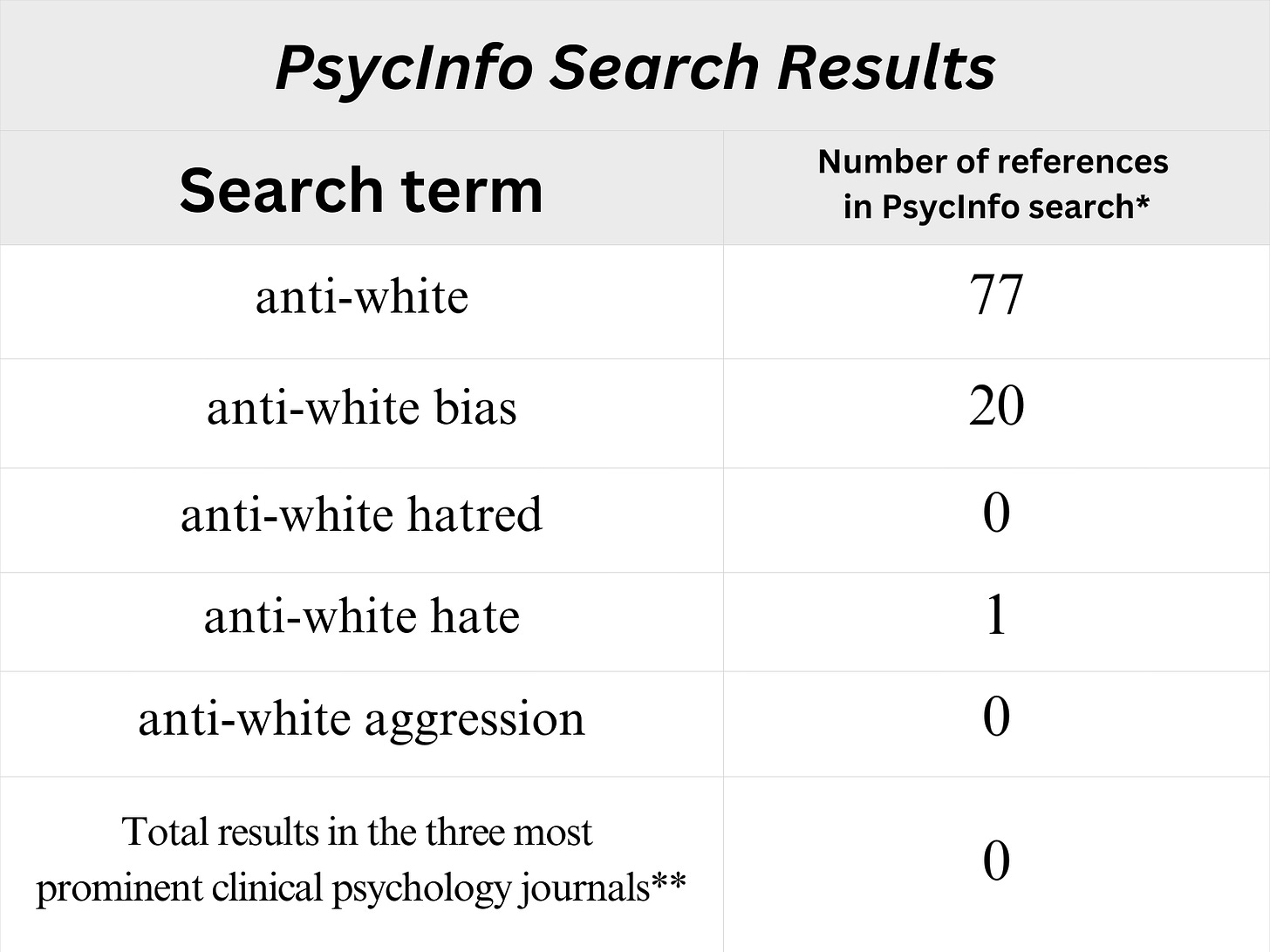

Research

A search of existing papers on this topic in the most common psychology database, PsycInfo, yields alarmingly few search results, none of which are in prominent clinical psychology journals (see Table 1 below). While academic research has focused on the prevalence, effects, and interventions in discrimination based on race, gender, and sexual orientation of other identity groups, there is hardly any research available where the group in question is white.

TABLE 1